Born of the elements

Out where the wind knows no fences and the light falls unfiltered across whole days of sky, people found out fast what mattered. Boots that could carry you through cheatgrass and shale. Saddles that wouldn’t betray your back. And a hat, a wide, good hat , that could hold back the sun, take the rain, and still be there come morning.

The cowboy hat, or more rightly, the hat of the range-rider, the herder, the field-walker, was never about fashion. It was about weather, and work, and the need to meet both with something that could stand its ground.

A new tradition in born

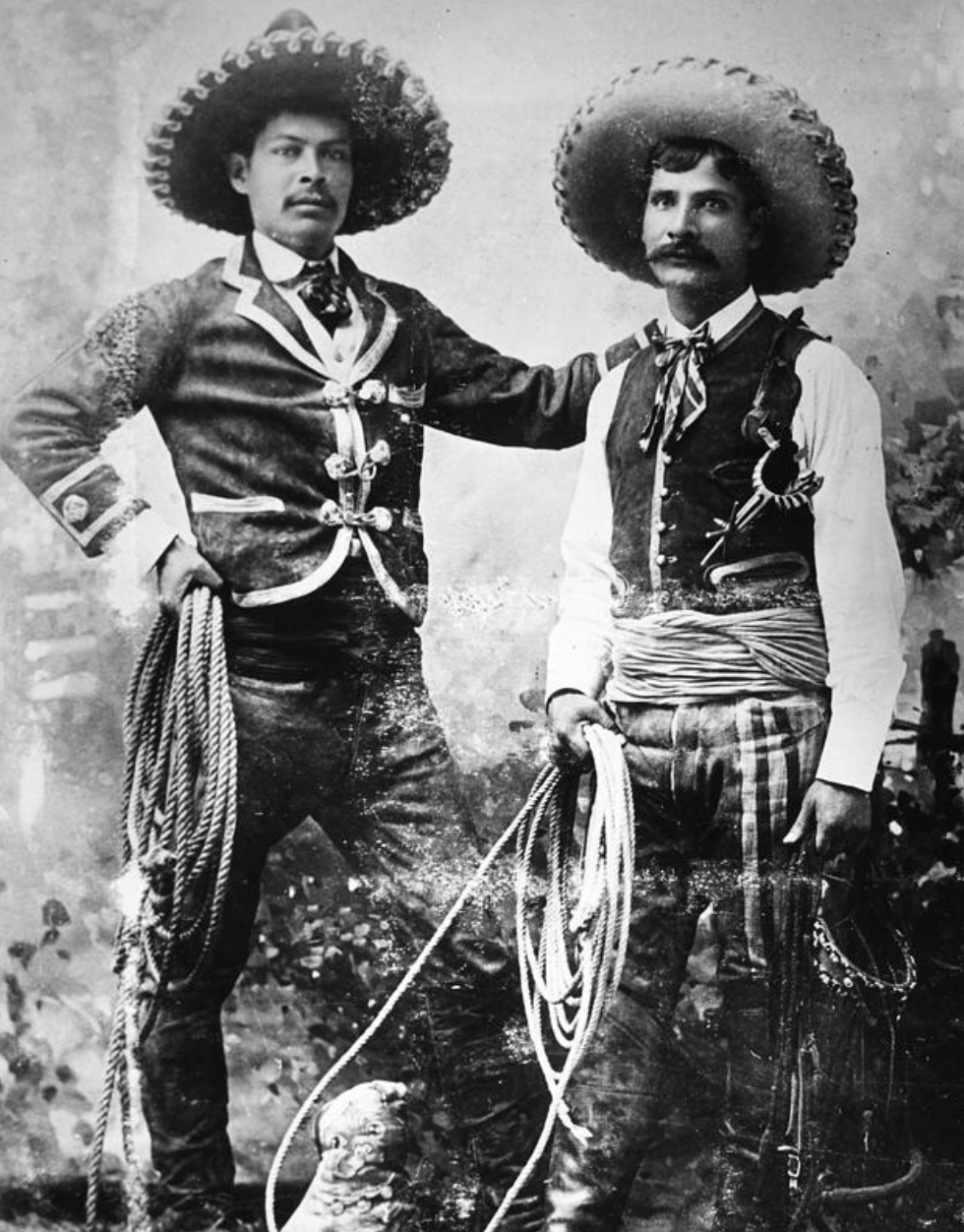

Like so many things the West claims as its own, the cowboy hat began far south of the 49th parallel. On the open ranges of northern Mexico, the frontera, vaqueros - master horsepeople and cattle workers of Spanish and Indigenous descent who rode in tall-crowned, broad-brimmed hats woven from palm and pressed from felt. The shape wasn’t a style decision. It was survival. Shade as shelter. Height as ventilation. Stiffness to fight the wind.

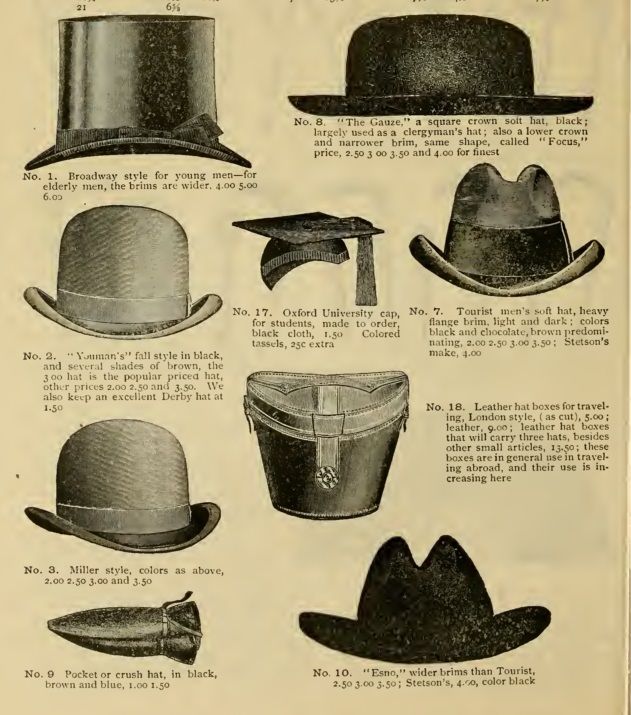

When Anglo settlers moved west from Tennessee and the Carolinas, they brought their own hats - derbies, bowlers, slouch caps. All of them failed in short order. On the Llano Estacado or in the Sonoran heat, the old-world hat designs had nothing to say.

What took root instead was an adaptation. A confluence of Indigenous craft, Spanish practicality, and frontier necessity. Not designed on paper, but in the hard lessons of exposure. The result was something uniquely Western. Not by birth, but by becoming.

In 1865, a New Jersey-born hatmaker named John B. Stetson unveiled a hat that would change the American West. Trained in the family trade but weakened by illness, Stetson had headed west for his health and found inspiration. Among Pike’s Peak gold prospectors, he noticed their headgear was all wrong for the elements: coonskin caps crawling with fleas, cloth hats soaked through in the rain, nothing that could stand up to sun, wind, or work.

So Stetson got to work. He shaped a broad-brimmed, high-crowned hat from fur felt—durable, waterproof, and ready for the frontier. Legend has it a passing bullwhacker paid five dollars in gold for the prototype on the spot.

That hat became the Boss of the Plains. Flat brim. Uncreased crown. No frills. It was a blank canvas, meant to be personalized, worn hard, and shaped by the lives of those who wore it. You could dip it in a stream to water your horse, fan a flame, swat a mule, then slap it back on and ride another hundred miles.

It wasn’t precious. It was built to last. And in the West, that’s about the highest praise a thing can get.

When Function Became Form

Over time, the hat stopped being blank. Across plains, mesas, and timber cuts, people began to shape them to the land and the labor.

In Texas, where the cattle ranches ran long and formal, the Cattleman’s Crease emerged, a tall crown pinched into three neat ridges. In Montana and the Dakotas, where blizzards came hard and uninvited, hats developed peaked crowns and broad, level brims that blocked snow and wouldn’t lift in the wind.

In the Four Corners, flat brims and sharp silhouettes spoke of old vaquero lineage, Indigenous innovation, and the unspoken codes of borderland ranch culture. Hats were passed down, reshaped, broken in and re-blocked, each one telling a different chapter, depending on the bend of the brim and the lay of the sweat.

And though no ledger recorded it, Black cowhands, Indigenous trail riders, and Mexican vaqueros were as central to this evolution as anyone, carrying forward techniques, materials, and meanings that remain folded into the felt today.

By the mid-20th century, the cowboy hat had become a kind of heirloom. At a time when plastic and polyester were taking over closets and factories, the felt hat held its ground. It represented something slower, more deliberate, and more real. Worn by Hill Country ranch managers, Basque herders in eastern Oregon, Diné riders rounding up sheep, and seasonal workers stretching fence from West Texas to Nevada, it wasn’t a fashion piece, it was a tool.

By the 1980s, after years of mass production and imitation, a quiet return to tradition had begun. Independent hatters across North America were picking up the old tools: wooden blocks, open steamers, iron flange plates, hand-stitched sweatbands. They worked felt the way it was meant to be worked, from beaver, rabbit, or wool shaping it not by machine, but by hand and feel.

What they’re making isn’t just headwear. It’s continuity. Hats built for a life of use, not performance. Hats that remember how the West was actually lived, in snowdrifts, branding pens, backcountry trails, and wind-burned ridgelines. And while today’s wearers may come from cities or studios as often as ranchlands, the best hats still carry it all, purpose, style, and a bit of story.

Wear It Like You Mean It

We still wear cowboy hats because they mean something, maybe more now than ever. They mean you take the world as it is, weather and all. That you know something about care and readiness. That you’re not here for fast fashion or easy explanations.

The hat doesn’t care where you're from, what you do, or how you identify. It only asks: will you wear it like you mean it?

At Hitmaker Hat Co., we craft each hat by hand, one at a time, the old way — with steam, pressure, and feel. Because the land is still out there. And it’s still working on us.

So we shape for those who move toward the storm, not away from it. For those who carry the past without being weighed down by it. For the headstrong.